Science-industry partnership revives fishery

Good things come to those who wait

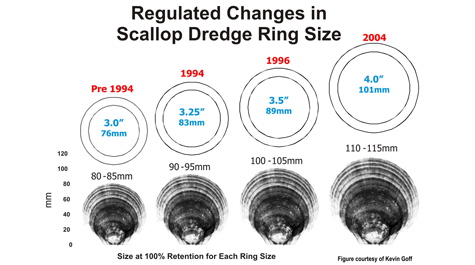

In the early 1990s, the scallop fishery along the U.S. Atlantic seaboard was on a sharp downward slide. Commercial fishermen were having to spend more and more time at sea, up to 240 days per year, but were catching fewer and smaller scallops.

Today, that fishery is the second most valuable commercial fishery on the East Coast, with more than $400 million in scallops landed in 2014. Virginia alone unloaded $33.6 million in scallops in that year, generating an additional $21 million in economic activity in the Commonwealth for a total impact of nearly $50 million.

A large part of the recovery and growth of the East Coast scallop fishery is due to a long-term collaboration between scallopers, fishery managers, and scientists at VIMS. The partnership, which continues today, was begun in the mid-1980s by Dr. Bill DuPaul, then director of the Marine Advisory Services program at VIMS and now a VIMS emeritus professor. The VIMS scallop program is now led by Dr. David Rudders.

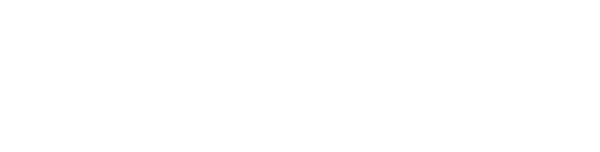

Rudders, DuPaul, and graduate students and technicians at VIMS have together spent thousands of days on commercial scallop boats and research vessels during the last decades, testing and refining dredge equipment to maximize sustainable scallop harvests while minimizing bycatch of yellowtail flounder and sea turtles.

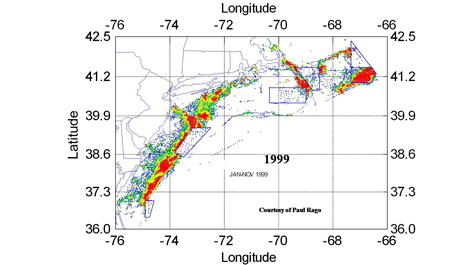

As a member of the National Marine Fisheries Service’s Scallop Survey Advisory Panel, DuPaul was instrumental in guiding development of a system of rotating closed areas that run from Virginia’s continental shelf waters northward to Georges Bank. This strategy allows scallop populations to rebound for up to 5 years following harvest.

“Traditionally, scallopers were harvesting animals at around 3 years of age,” says DuPaul. “Closing an area for 5 years allows them to take advantage of a scallop’s rapid growth between 3 and 5 years of age, when the animals more than double in weight. By waiting, the scallopers get more meats per shell and a more profitable product.”

The collaboration between scientists and fishermen hasn’t always been smooth. “When we said that they could harvest twice as many scallops in half as many days, that was a hard sell,” says DuPaul.” But the groups have developed a mutual respect, based on the success of the program and a healthy dialogue in which each side was willing to listen to the other.

Fred Mattera, a Rhode Island fisherman and former member of the Northeast Cooperative Research Partners Program, lauds the contributions that DuPaul and his students have made to the scallop industry, noting that their work helped turn a struggling fishery into a model of sustainable profitability for the entire eastern seaboard.

DuPaul attributes his success in large part to “continuity of presence.” “We’ve been working with scallopers for more than 30 years,” says DuPaul. “That’s given us time to understand their needs, and for them to develop trust in the science.”